HISTORY

INTRODUCTION

The Suburban was founded in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, IL in 1999 and relocated to Milwaukee, WI in September 2015. The Suburban is a project space that honors the tradition of artist directed programs.

Michelle Grabner & Brad Killam

A SUBURBAN PECULIARITY FOR A TEEN

One of the first things my Advanced Placement European History teacher, who I have grown to thoroughly respect, said to us, came in a class discussion about about the children of historical figures. "I want each of you to go home and thank your parents for not being artists," she said. "The children of artists are the ones who lose their minds, fall into madness or commit suicide, and I wouldn't want any of you to turn out that way."

Her commentary was obviously striking: I am not only the child of two artists, but I am constantly surrounded by art and its supplementary activities (its viewing, selling, and making). The nucleus of this part of my life lies in the tiny yellow building formerly attached to my garage. My parents call it The Suburban.

The Suburban is a social perculiarity that I have not yet learned to cope with. Since its conception in my preteens, The Suburban has created a varying array of effects on my life, the majority being positive. I have dissected my entire record collection with a British artist named Simon, I have shared fruity non-alcoholic drinks with my friend Sam at a fully functional tiki-bar-cum-art-installation, and developed to some degree, an understanding of what constitutes contemporary art.

However, life within intimate proximity to an art gallery is not entirely beneficial for a self-conscious teenager and his ten-year old brother. While awkwardness does arise when sharing a house with half-a-dozen large, unshaven Scandinavians, the major difficulty of living with The Suburban is explaining the idea and function of it to the more tradtionally "suburban" mothers of my friends.

"Were your parents throwing a party at your house on Saturday?"

Yes, it was an art opening."

At this point I try to convince her that The Suburban is a serious pursuit of my parents, and that is has a "real" significance in the art-world. What this significance is I do not know.

Among my peers, The Suburban has brought me neither recognizable fame, (I can't imagine "My garage is also an art gallery" would serve as a successful pick-up line) nor overwhelming scorn. My general rule is to discuss the gallery and its work only with close friends or those who question what "The Suburban" means on our household's telephone answering machine prompt. My reasoning for this is simple; debates about the artistic merit of a fictional Swedish Citizen Recruitment Center are not something I enjoy taking part in, let alone fully understanding.

Because of The Suburban and my parents' choice of career and life style, I have seen and learned to appreciate art on levels unknown to my peers. From Marfa, Texas, to Budapest, I have traveled the world to see it. I have eaten bratwurst in my yard with those who make it. I have traded my bedroom away for weeks to Englishmen for duty-free tubes of Toblerone chocolate. For this uncommon exposure, it should have been the request of my history teacher to come home and thank my parents for becoming artists.

Peter Ribic

WESTWARD HO!

SNAPSHOT: LATE '90S: THE WINDY CITY

For a town of its size, energy, and wealth, Chicago's contemporary art world was remarkably small. With just two-and-a-half serious institutions dedicated to visual culture, a single "blue-chip" gallery that survived by cherrypicking the programs of its larger competitors on the coasts, few committed collectors, and one wobbly media organ (since defunct), America's third largest city struggled to support an active community of first-rate contemporary artists. The lack of a thriving commercial gallery scene deprived Chicago's artists of the financial clout needed to strengthen their aesthetic hand; without the fuck-you money that underwrites hard-core imaginative independence, they were vulnerable.

Power resided elsewhere. What few career opportunities the city was able to muster were controlled by a small band of local academics and arts administrators who collaborated, reinforced each other's authority, and vacationed together. During their reign, the Chicago art world - like the eternal, ruling Democratic machine after which it was modeled - gradually evolved into a profoundly inorganic operation.

For those artists, curators, journalists, and gallerists who were not favored by the ruling forces, the situation was sclerotic and depressing. Not surprisingly, pathologies surfaced in the local artist corps. One type of artist, desperate to forge some connection to those places that could advance them, privileged A Career Full Of Right Moves - the glorious world of strategy, career politics, and social maneuvering - over the vulnerability and generosity that good and original art willingly risks. In the alpha group's shadow wandered the majority of Chicago artists. Unwilling to define their self-interest as narrowly as their more ruthless peers, and so forced to accept what career crumbs were left them, many of these artists contracted a chronic case of the sours. Neither emotional style was the sort to inspire an abundance self-respecting, first-rate imaginations to sign on. An exodus of artistic talent annually set out for one of the coastal capitals.

FRESH AIR

In '97 Brad Killam and Michelle Grabner moved down from Milwaukee - a city without a commercial contemporary art scene and thus one devoid of professional hoops to jump through - to teach in Chicago and raise two boys in suburban Oak Park, an affluent suburb immediately west of the city line. Plunging into their new hometown with their trademark energy and drive, Killam and Grabner quickly gained first-hand experience of its art scene's sorry condition. If they were to improve their odds of living genuinely happy lives as participants in the Chicago art scene, they'd need a way to finesse the flaws in the local set-up. That much was clear. The couple determined to establish some sort of non-commercial exhibition venue that, whatever the particulars of its program, at least felt better.

They did have two specific antecedents in mind: Stephan Dillemuth's Friesenwall project, active in Cologne during the early '90s; and Matt's Gallery, which had been operating in London since '76. Both were ventures that explored the idea that the specialized real estate known as "a gallery" isn't just a place for hanging pictures but is, rather, a context, with that context's definition conforming to whatever happens to be introduced into it. To these influences was added a third, courtesy of yours truly. For some years it had been my own fantasy to open an avant-garde art gallery in a suburban strip mall. I'd voiced that desire in the couple's company more than once, and it was added to the mix of ideas that eventually coalesced in Brad's own eureka moment.

Attached to the garage of the modest Grabner/Killam home in Oak Park was a tiny, eight-by-eight foot room with cinder-block walls, into one of which was set a big window with eight segmented panes of hammered glass. Previously the room had served as a storage shed; Brad saw that, without too much trouble - emptied, cleaned, painted, some inexpensive illumination added - it could be reborn as an exhibition space. Although minuscule, the new venue, dubbed The Suburban, could still provide a power base sufficient to reduce his and Michelle's reliance on the unhealthy Chicago system. In their own backyard, the two had located a place that could be used to invite into their lives the tenor of experience they sought.

An avant-garde gallery in a suburban garage in the Midwest: it felt like a natural development. In fact, since art is fond of money and the suburbs have money, it's curious that there aren't already a lot of artist-run avant-garde galleries scattered throughout America's countless suburban communities. But there aren't. True, the Los Angeles art world has managed to shift things in this direction somewhat (Thomas Solomon's Garage comes to mind, but likely there were other LA garage-galleries predating his venture), if only by virtue of the fact that, in all the sprawl, the distinction between city and suburb is, integrally, blurrier. (The Suburban has more in common with the LA model than with New York's.) LA's example notwithstanding, the art world's habit of identifying artistic experimentalism with urban income and lifestyle diversity is firmly entrenched; the avant-garde's history is principally a history of marginal neighborhoods in large cities - and has been, ever since it emerged as a self-perpetuating cultural artifice at the latter part of the nineteenth century. After more than a century, though, the idea of clustering cool galleries in urban art ghettos is about as original as the cycle of gentrification it's known to spark. It's time to be looking at other, more enticing locales.

Artists are expected to dislike and ridicule suburban life, of course. It's practically a responsibility, a duty, this attitude. Suburbs are too plastic or too dull or too conformist or too...something. Or is it that they're not something enough? I never know. I remember, sometime in the '80s, hearing the hard-core Manhattanite Gary Indiana remark that the suburbs should be burned down. I also remember wondering what in the world he was talking about.

I didn't get what the guy was talking about. I'd been under the impression that artists were people who had a predilection for frontier living, and, well, aren't the suburbs a sort of frontier?

Situating a gallery for experimental, avant-garde-ish art in the garage of an American residence in the suburbs, then, actually constitutes a frontiering act on two levels. The fact that, physically, the suburb represents a new (in America, at least, the mass, middle-class suburb is barely fifty years old) category of landscape - Trees 'n Traffic! - is only the more obvious of the two; the idea that an adventurous, creative American imagination might not automatically loathe or reject that new style of environment is itself imbued with a definite pioneering dimension.

In Brad and Michelle's Suburban project the romance of the olde American frontiering impulse had taken fresh form. By inserting the context of experimental visual culture amid its leafy streets, the suburb's image of itself was challenged, and altered a little bit. At the same time, extending to the 'burbs a gallery of The Suburban's stripe confronted a few of the avant-garde's own self-limiting assumptions. Westward ho, indeed.

2003: The Suburban has reached its fifth season of operation. Presented six or seven times a year in its sixty-four square feet of space are artists known and unknown, American and European, young and old, hailing from places cool and uncool. As with any other gallery, sometimes the shows are good, sometimes less good. When an Important European Artist is exhibiting, one or two of the lieutenants in the Chicago machine make the right move and attend. Everyone's welcome. On clement evenings the openings are held outside, fifty or so well-behaved, friendly, slightly beery people milling about on the lawn. Even in subzero temperatures, Chicago's artworld feels a little warmer.

David Robbins

THE NEXT FIVE YEARS

The moveable roof tipped me off. A clever nod to the worldwide museum-expansion frenzy of a few years previous, Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam decided to go for sub-grandeur in their maturing art gallery's third expansion.

The self-styled proprietors of The Suburban exhibition space in Oak Park have always been comfortable with the meshing of large and small scales. A compromise between their internationalist art ambitions and their lively life as a well-knit family of four, they opened the tiny gallery in a backyard outbuilding space originally intended as the office for a two-bay commercial garage.

Artists responded well to the space, balancing the demands of the solo show format with the adroitly manageable 8' x 8' room. For instance, Gaylen Gerber's normally monumental wall-filling Backdrop received a new treatment here, and a new reading, situated on the tiny back wall of The Suburban. Because the painting felt like it had been cut off at either end by The Suburban's narrow walls, I at once realized his Backdrops weren't discrete paintings at all, but one giant painting spread out over space and time, and this smaller-scaled entry wasn't a version but a continuance of the overall project.

Obviously, with so little room available, the original Suburban held no more than a few viewers at a time. The inset-swinging door proved as challenging for negotiating the space as did a gaggle of more than two or three visitors. The inevitably cramped situation made for a kind of reverential art experience, with viewers stepping inside singly or in appropriately small groups, closing the door so as not to be interrupted. For me, the experience resembled something like being allowed into a precious archaeological site, or filing in for a glimpse at a revered and priceless historical document. Because the gallery is too small to accommodate opening-night crowds, receptions inevitably spilled into the yard and the main house. Instead of a typical art opening, a Suburban reception felt more like a breezy backyard barbecue.

So the initial expansion of the space, into what had previously been the couple's shared (and far more roomy) art studio immediately adjacent, seemed at first a risk to The Suburban's fragile ecology. I wondered how artists, some of whom had been looking forward to the chance to tackle the gallery's unique display challenges, would respond to a less limiting situation. Like deadlines, guidelines and budgets, limitations can be ultimately freeing, and most artists proved the point by mounting extremely well-conceived, appropriately-scaled shows.

Subsequent shows made the expansion a non-issue, with deftly handled installations by Julie Mehretu, Sarah Lucas, Joseph Grigely, Olafur Eliasson, Aleksandra Mir, Pierre Huyghe and Ceal Foyer. Having so many national and international artists accept invitations to show, Grabner and Killam responded by accommodating the next natural evolutionary phase of the gallery: The Suburban residency program.

With the footprint of the original building defining the limits of expansion in the tightly-zoned Oak Park neighborhood, building upward was the next logical step. The new second story allowed room for two studio spaces and two apartments, where artists-in-residence could live and work as both part of and separate from the Grabner/Killam/Ribic family. Remaining independent, the residency program was funded by occasional regional and international grants, along with the ever-open economy of the Grabner/Killam working household. Just ask the resident artists how good Michelle's homemade pizzas can be after long days of conceptual meandering.

The Matthew Barney/Bjork residency changed everything, of course. When the uber-avants chose The Suburban over the Art Institute of Chicago to birth their costumed-in-the-womb child, they made not only their own familial evolution but also helped bring the Little Gallery That Could to full maturation. In shunning the city's grand art behemoth, Barney and Bjork also flipped long-accepted local codes of institutional supremacy.

To celebrate The Suburban's newfound status as a triumphal model for independent art spaces, Grabner and Killam chose Scandinavian art collective N55 (Suburban veterans from 2001) to construct a moveable roof that also doubles as a solar- and wind-powered generator to provide electricity for the entire campus. Opening to the fresh air like the renowned Miller Park roof in Milwaukee to the north (and its more elegant cousin the Milwaukee Art Museum), The Suburban roof now literally lets in sunlight to a figuratively underground institution. Though daylight and fresh air will most certainly be appreciated by the artists who will come to spend summers there, one may again fairly wonder what effect this brightening and broadening will have on the Chicago area's most vibrant guardian of the vanguard.

Like the Milwaukee Art Museum, The Suburban now also boasts a crown - one whose design is not dictated by the necessities of displaying the artworks within, but one that freely announces the place as an artwork in its own right. But The Suburban has really always been a kind of art project. Since the supercession of institutional curation by free-agent show organizers, art programming has come to be regarded as an art practice, melding with the now commonplace mode of artists who use the work and efforts of others as material for their own work. The idea is that curators are as important to shows as the artists, and that over time, the programming of a particular space can be seen as an idea-based collaboration between organizers and artists.

Michelle and Brad have themselves worked collaboratively as artists for years, first as CAR, which took the whole family (including sons Peter Ribic and Oliver Killam) as fodder, subject and equal generators, and so we should naturally think of The Suburban as a large-scale, immersive and inclusive project. The continuing physical expansion of the space, rather than a threat to the sanctity of the original intentions of The Suburban, is actually a perfectly suitable manifestation of the founding spirit of the place. Their own family might be small, but their metaphorical family includes an ever-expanding world of interesting artists and audiences.

So, let's celebrate not only the past ten years of The Suburban, but look forward to the next five years, and heck, the next fifty years as well. Oak Park might be cramped, but you can always build up, you know. Solidly against the ideas of former resident Frank Lloyd Wright, who eschewed skyscrapers in favor of suburbs sprawling out over the rolling prairie landscape, Michelle and Brad's plans to add a third, fourth, and possibly more stories to what must now be called "The Suburban complex" seem wholly appropriate for a new era. Today's Oak Park lawns may be narrower, but its best minds are broad indeed.

Nicholas Frank

Michelle Grabner & Brad Killam interviewed by David Robbins about The Suburban gallery

June 20, 2010

MG: A lot of it had to do with pragmatics, and with what we inherited when we moved to Oak Park. The property we bought there in '97 included a funny little outbuilding adjacent to the garage. We parked the lawn mower in it for the most part but we also knew that it had some kind of potential. At only 8 by 10 feet it was a little too small for a studio...

DR: And the thought to turn it to some other use...?

BK: There were a few other galleries or exhibition places that you could point to and think, wow, that's interesting, that's not the usual thing. Thomas Solomon's Garage in Los Angeles was always interesting, Los Angeles was a natural place for a different exhibition venue to pop up because LA is so decentralized and so much of it is suburb-like in terms of street plan and architecture. Another model was Matt's Gallery in London, way out in the East End before the East End had any galleries. We also liked what Gavin Brown had been doing early on, making exhibitions in pubs. Steven Pippin made exhibitions in an office space in a Manhattan high-rise, you had to check in and ride up in the elevator and all that. All these were outside the norm and all were appealing and interesting. Their existence reinforced our instinct that we could use the little building in our backyard for something a bit...off.

MG: Thinking in terms of making exhibitions wasn't that unusual for us. When we were living in Milwaukee, in the years prior to the Oak Park move, we had put together exhibitions, inviting people like Tracy Emin who we'd seen in Frieze, which would come to our home mailing address. Artists were responding to our requests. When we moved to Oak Park we just continued asking and offering. And a lot of it had to do with your thinking, too, David, after you'd moved back from Europe to the Midwest. "Here we are in the middle of nowhere, away from the center, let's try something different. "

DR: At that time I was taken with the idea of opening a contemporary art gallery in a suburban strip mall. That location was so "wrong" something about it just had to be right. Why had I never seen a contemporary art gallery in a suburban strip mall, housed in that kind of architecture, instead of the usual clustering in urban neighborhoods? In New York or Chicago or Boston some people of means and education will live in the city but in most of the country they live in suburbs. And if, presumably, your audience is people of means and education who can perceive the value in contemporary art and support something called a contemporary art gallery, then why is it such galleries still consign themselves to art ghettos--clusters of galleries in, very often, run down parts of urban neighborhoods where artists congregate? Right there's your answer, of course: those neighborhoods are where artists, especially young artists who seek dialogue and want constant reinforcement of their lifestyle choice, congregate, even when doing so is ghettoizing. Still, the idea of an experimental gallery in a suburban strip mall suggested a host of questions as to why galleries are situated where they are and whether that can be altered or added to. Also, at that point, 1997 or '98, one had to recognize the decentralizing force of the Internet. Not even twenty years ago, if, as an artist, you wanted the kind of information around which contemporary art coalesces, you'd move to New York or LA in order to interact with people who produced such information. The Internet, though, obviated the need for that move, and disrupted that pattern. Now the disparity between the information that you had living in New York and the information that you could get living in Oak Park is no longer that wide. That, too, informed questions about whether you could have a venue to show the kind of thing we were interested in, away from the traditional centers...

MG: When talking about The Suburban I often evoke Frank Lloyd Wright's choice to open his studio in his Oak Park home and to no longer take the train downtown to work for Louis Sullivan. A hundred years ago that was a fairly radical decision. The suburb was not where anyone would have expected a whole new visual vocabulary to bloom. So there is some history in terms of using the suburb as a base, a starting point.

DR: Good point about Wright. And we might include Charles and Ray Eames here too. But mostly artistic experimentation happened in cities, being loci of economic diversity and cosmopolitan sophistication. The existence of a contemporary art gallery in the suburbs thus confounds two traditions. One tradition being the perception that the suburbs are merely places of complacency, safety, and child-rearing that don't generate adventurous information culture.--

MG: Right. The suburbs have a construction already and we just don't make room for imagination there.

DR: --and the other tradition being the avant-garde's disdainful attitude toward the suburbs. The Suburban complicates both those traditions. The two models of the avant-garde that have been dominant during the modern period are, on the one hand, the cosmopolitan, hyper-urban, sophisticate embodied by, say, Warhol, and on the other, the George O'Keefe model, where the artist goes into the wilderness for a more direct relationship with the natural world. Both of these models reject the suburb. Underexplored by artists, then, has been the space in between, the suburban blend of city and country that I like to characterize as "trees and traffic," that sort of balance or hybrid. It's a place where a lot of artists come from but abandon once they learn the specialized language of art and begin producing a class of objects whose uselessness resonates within the diversified economy of the city. For all these reasons, to me it's interesting to explore being a producer of contemporary information from a suburban setting.

MG: Whether it's the Southwest or Manhattan, there are too many artists and not enough audience. The arts are overbuilt in some places and underdeveloped in others.

DR: The mere existence of The Suburban, situated where it is and performing as it does, suggests a change in some long-standing patterns, then. When the city becomes so expensive that you have to work all the time just in order to pay the rent to keep living there, then at least some intelligent, creative people are going to choose out of that. It's easier now to do so because of the Internet.

MG: People who have agency and control discourse don't see it in these terms. The NEA still sees the arts in terms of revitalizing, say, Woodward Avenue in Detroit. So after ten or eleven years, or after Matt's in London, or Thomas Solomon's Garage, the idea of a contemporary art gallery in the suburbs which aspires to something other than revitalizing a depressed neighborhood is still relevant as an intellectual question.

DR: Ten years in, The Suburban is still a pioneering effort. Who is your audience?

BK: We didn't set out to determine a business plan to draw a certain audience. The audience has happened the way it has happened, and it's primarily artists. The plan was to make exhibitions that relied neither on commercial considerations nor on the non-profit grants process. The whole point was just to make exhibitions that had neither one of those pressure points determining some or all of what happens. We didn't want decisions to be based on a potential sale of a work or on this grant or on that patron giving x amount of money for such and such a program. So, apparently, if this is a ten year test case, artists are more interested in quote unquote "pure exhibitions for exhibition's sake" than is any other demographic or audience.

MG: Brad and I are artists who also teach, and a good percentage of people who come to Suburban shows are students, but there's also a tourist element. Tour buses pull up in front of the house full of people from the Seattle Art Museum tour group who are on their way to see the Wright studios. Yet curators still won't come out from downtown Chicago! Curators and collectors in Chicago won't make that twenty-minute commute to Oak Park to check out The Suburban but we'll have people fly from Southern California or Birmingham, Alabama, or Seattle!

DR: That says a lot about their agenda.

BK: We have enjoyed the idea that we are presenting another type of exhibition experience. Physically it's not that much different: there are white walls, there's a painting on the wall. But because of the framework of The Suburban being neither this nor that--

DR: Like the suburb itself, neither city nor country-

BK: --it presents an alternative to commercial or non-profit spaces.

DR: Has it always been entirely funded by you guys?

MG: Yes. On occasion we will have someone coming from New Zealand or Denmark to whom we will write a letter of invitation and they can solicit some money from their state--

BK: --which may cover their airfare. But otherwise there's nothing.

DR: How is your relation with the commercial galleries who represent many of the artists you show? Is there friction?

BK: There is. We're adding another wrinkle to their inventory management. There always seems to be a little friction in that regard. No matter what and no matter how smoothly the whole exchange can go or will go or did go, there always seems to be something that's a little big niggling.

MG: Commercial galleries have a particular way of valuing work, and the art needs to be handled in a way that is consistent with that.

BK: Sometimes a big old gorilla stomp happens too!

MK: That's mostly with the really big galleries. The other side of it, though, is that I think commercial galleries actually value The Suburban. We don't represent that artist, we're giving that artist a chance to show in Chicago which they otherwise might not have had, we're not going to want to hang on to that work or take that artwork to a fair, so in a way we function as perfect outreach. Most artists are sort of chomping at the bit to have exhibitions elsewhere, and The Suburban is safe for them. And that's valued.

BK: We don't have a relationship with the gallery, we have a relationship with the artist.

DR: Have you ever sold anything out of The Suburban?

BK: We 'facilitated' three sales in ten years.

MG: However rough the relationships with dealers over the years, artists more than make up for that.

BK: It should also be noted that the majority of the artists who show at the Suburban usually live in other cities and usually pay their own travel costs to come to the opening. It's rare that an artist isn't at their Suburban opening.

MG: I'd say only 5% in the ten years haven't showed up and installed their own work and made the opening. That's impressive.

BK: From all over the world. For the artist to dedicate their time and resources to be part of it really makes it a special event.

MG: Quite honestly that's the only way that the context of The Suburban as a space and a social construction, or the relationship between public and private that The Suburban puts forward, or coming to the Midwest gets negotiated. So for artists to show up and see how their work is contextualized within this other frame means a lot. Let me say that, not surprisingly but still disappointingly, it's the younger artists who just want the Suburban on their resume that give the least of themselves. The artists who have established careers have really been extraordinary in their generosity.

DR: More mature artists really understand the difference that The Suburban represents.

MG: That's right.

DR: You've shown a range of artists--some just out of graduate school, and some, like Luc Tuymans or James Welling, with very established careers. How do you go about identifying who it is that you want to invite to exhibit? You're not doing it because you're going to make money from the show, so that incentive has been taken off the table.

BK: To a certain degree it works like the rest of the art world. It's not all that innovative in that regard. You meet somebody at an opening, you have a friendly conversation, you run into them again a year later, you invite them to show, and two years later it happens. Some combination of that normal networking process...

MG: It's directly related to our movement through the world and who we've encountered, and laying out an invitation to those people. We were traveling to Helsinki or wherever as invited visitors and ran into so and so... They have to kind of get what's going with The Suburban, have a full understanding of its limitations, the public/private, the suburban context, the space, the miniscule budget... We don't make pitches to anyone.

DR: To try to raise the gallery's profile...

MG: To what end? Right. Nor do we extend invitations based on unsolicited proposals from people who have never been there-"I'm interested in your program from what I've seen on the web." Never happens. Frankly we don't get many people sending us slides. We maybe get two or three submissions a year... European artists send four or five catalogues in a box! Apropos inviting artists: since 2003 we've had two spaces--one small, one very small--that run concurrent exhibitions. Sometimes the two invited artists would converge in Oak Park and maybe not get along or there was confusion about who got what space. We alleviated that by inviting one person and letting them invite a co-exhibitor.

BK: That was Michelle's idea, and that could be one of the more innovative programming things that happens at Suburban, because it does happen regularly. Andrea Bowers suggested Marcos Ramirez ERRE, and so on. The list is long.

MG: It opens up a lot of territory for us. For instance, Jeff Gibson, an Australian artist based in New York, asked if Jeff Kleem an artist from Australia, could show with him in another space. This kind of "program" introduces us to other people while allowing us to avoid interpersonal conflict. The two artists then have the option of integrating their work in both spaces. Walead Beshty and James Welling did that.

BK: Lars Wolter and Dan Walsh literally collaborated completely on showing in the two spaces, but that is the rarest example.

MG: Most artists just sort of go to their space and deal with that. Which again reinforces an unfortunate reality of the art world, which is that even in a tiny space in the suburbs the artist will take possession of their exhibition and their work.

DR: "I am the author of this space..."

MG: Yes!

BK: There's nothing wrong with that necessarily.

MG: Well, it's pretty predictable.

BK: Have a little sympathy for those predictabilities! Maybe the artist is having an off year or hasn't shown in a while, and they want to stand out.

DR: Letting other people invite their co-exhibitor loosens your authorial grip on the space...

MG: Absolutely. It's a way of acknowledging networking, another force that actively shapes the contemporary art world. We move through and our careers progress through a kind of web. That's been part of The Suburban's reality all along. I have been very vocal about not being a champion of the contemporary curator. When you run an art space, having to invite even one person is a curatorial exercise. That has always made me uncomfortable even though we let people come and do whatever they want and don't select the work that's exhibited. Running an exhibition space, there's no getting around a certain curatorial aspect but there is a way of sharing it.

DR: Diluting it...

BK: It's an interesting dilemma to operate an art space and keep looking for new ways not to be the curator!

MG: While maintaining quality, and the integrity of all the things we're talking about, and keeping them front and center. How do you do this and not compromise some of these critical interests that we have while at the same time avoiding the trap of "branding"?

DR: "We don't show that kind of thing here."

MG: Right.

DR: How would you characterize the kind of work that you do show there, the general affinity...?

MG: "Contemporary practice."

BK: I don't have a name for what we do show but there's plenty of stuff out there that we prefer not to show.

DR: Someone who has never been to The Suburban might say, "I'll bet they show outsider art there."

BK: We show insider art.

MG: That's one boundary. I think that's right.

DR: Inside...what?

BK: Inside the loop of what you, David, have characterized on many occasions as "the international avant-garde."

DR: Art that seeks to advance what art can be.

MG: We're inside the loop but we're all over the place too. An invited artist may come from New Zealand or Berlin or Milwaukee but still work within a recognizable insider relationship to international art making, that information set.

DR: Which of course points to the rise and acceptance of a language, a specialized language learned in art schools and university art programs that together release thousands of artists into the marketplace each year... Fifty years ago were there thousands of artists trained in a visual language of something called "contemporary art"? No. It was a tiny community. But today it's a language used everywhere there are artists. If the Suburban, because of its setting, offers a context that can be interpreted as an opportunity to introduce something different, we also discover what doesn't change. We discover shared thought and shared values but also shared suppositions. The Suburban has been a means of channeling a bit of art world traffic through a space in your backyard, but to some extent it's the same traffic as elsewhere. Which says more about artists than it does about The Suburban.

MG: The cultural questions set in motion by The Suburban don't get resolved immediately, nor should they be. To give you one example: the Shane Campbell Gallery occupied one of the spaces in The Suburban complex before opening a space downtown. Local collectors told him "you better have a space in town because we're not going to come out to Oak Park." They'll buy in New York but they're not going to get into a car, because they live downtown in a high rise, and come out to Oak Park! So it's weird. It's not resolved. Also, I hear about a lot of small spaces starting up, in Richmond, Virginia, or Des Moines, Iowa, they're not suburbs but they're off-center. But they're usually tied to a school. Where artists are, where artists work, the places where artists can afford to have space to work. But the idea to take into account the ideology that supports what the suburb is today, whether it's Chicago or New York or St. Louis, it's still not engaged by artists

DR: This is exactly what I was pointing to ten years ago! How to reveal the ingrained ideas and assumptions shared by artists about art? I know that it isn't The Suburban's charter to reveal these tropes but in the process of The Suburban going about its business, tropes do get revealed. What anyone wants to do about them is of course an open question. In their projects for The Suburban, have any artists thematized the setting-"a contemporary art gallery in the suburbs"?

BK: A few. When Meg Duguid draped our yard in 300 rolls of toilet paper, she definitely zeroed in on a suburban phenomenon: the tradition of toilet-papering the front yards of the homes of particular students at the beginning of the school year or for the homecoming weekend.

MG: Jeanne Dunning's big inflatable "thumbs up" that used the same visual advertising grammar seen at car dealerships certainly played into the drive-by car culture of suburbia. When artists choose to install their projects in our yard as opposed to retreating into the white walled space, often that's the work that, because it's clearly situated at the intersection of private and public, most directly uses the suburban context as a material. Otherwise I'd say the "suburban" theme has gone largely unexplored. . Artists don't take it on as a specific construction. Artists will take on sites, but those sites are usually within their reach, whether the site is in Iowa or Virginia or Oak Park, Illinois. So that too is something that still hasn't resolved itself culturally.

BK: Shows at The Suburban seem to fall within one of three zones. In the first, the artist breaks off a little piece of their production and sends it to The Suburban.

MG: Which is perfectly fine. Garth Weiser might do a wall painting that is very similar to a wall painting he did six months prior at Casey Kaplan Gallery in New York, but in this other location he's expecting another kind of feedback, right? So when you transpose the same thing into different contexts, something interesting happens.

BK: "Let's see how this plays in another context..." Then there are the shows where an artist presents a minor-key aspect of their production that they see as a good fit for The Suburban.

MG: Right. Trying something out that they haven't tried in the more official venues yet. Examples would be David Reed and Ann Pibal. David Reed showed his drawings-studies which he'd never exhibited prior to The Suburban, after which he then had a full exhibition in Europe. Ann Pibal had been doing collages down in Mexico, she wasn't quite ready to introduce them to her New York gallery but she thought that she could try them out here and see what the response was. That's ideal, when artists can see the space in that way. But not everybody does. I would say that it takes a secure and questioning artist to be able to use The Suburban in ways that not only can contextualize their work in a suburban location but actually pose questions that they have about their own production.

BK: The third exhibition zone is when somebody who might have a very straightforward successful practice decides to really jump out of their skins and make something that is completely uncharacteristic of their own work-a painter making, say, a video.

MG: Artists can come here, they can do whatever they want, we're not working with them in terms of a commercial gallery's needs. We give them the space but we don't give them conditions, and compared to an institutional show their show with us happens relatively fast. So a different set of values maybe supports the same work, and it's left to the artist to decide which they prefer. An exhibition at The Suburban is more closely related to what happens in your studio than to a proper exhibition at an institution. You have to succeed and fail the same way you do in whatever studio construction you have.

BK: I can say for myself that I don't think I framed The Suburban as "now we can bring the artworld to us." I think probably in my bad attitude kind of way, I framed it as "we can do it better."

MG: Or we can do it with a different set of conditions and values. Ultimately we see The Suburban as a grand experiment, and we will tread very far from our own studio interests to discover what that experiment can hold and explore. It's not exclusively about enriching our own studio practices or our teaching. To see how other people engage ideas, even if it's an idea that we keep distance from in our own work, is hugely important.

AN ONLINE PROJECT

The Lives of Objects at The Suburban, Mieke Marple, 2009PRESS General

- Suburban Milwaukee Saturday Night Fever Lise Haller Baggesen, Bad at Sports, 2015

- Tiny, Mighty, The Suburban is About to Be No More Christopher Borrelli, Chicago Tribune, 2015

- Before Moving to Milwaukee, Michelle Grabner's Oak Park Garage Gallery, The Suburban, Makes a Pit Stop in Indianapolis John Chiaverina, Artnews, 2015

- Near and Far Jennifer Kabat, Frieze, 2015

- The Suburban Re-Opens Gallery Space This Weekend Matt Morris, NewCity, 2014

- Off-space No 21: The Suburban, Oak Park, Illinois Karen Archey, Art Review, 2014

- In Conversation: Michelle Grabner and Barry Schwabsky Brooklyn Rail, 2013

- By Appointment Only: Viewing Art Privately In Chicago Jason Foumberg, Art In America, 2013

- The Great Suburban Frontier, Zachary Johnson, The Chicago Arts Archive, 2011

- Michelle Grabner and Brad Killam Artforum, 2010

- The Suburban: A Space for Contemporary Art in Oak Park, Illinois Claudine Ise, art21 Magazine, 2010

- Suburban Makes Its Mark On The Urban Scene Lauren Viera, Chicago Tribune, 2010

- Interview with Michelle Grabner Mieke Marple, The Highlights, 2009

- David Hullfish Bailey At The Suburban Bad at Sports, 2009

PRESS Exhibitions

- Polly Apfelbaum and Stephen Westfall 2015

- Fergus Feehily and here 2015

- Russel Maltz and Victoria Munro 2015

- Mamie Tinkler & Winslow Smith 2015

- Evan Gruzis 2014

- Dana DeGuilio and here and here 2013

- Gabe Farrar and Siebren Versteeg and here 2012

- Marie Mason and Kelly Poe and here 2012

- Sara Greenberger Rafferty and Ruby Sky Stiller and here 2011

- Diego Leclery 2010

- Hilary Wilder 2010

- Andrew Falkowski and Karl Erikson 2009

- David Hullfish Bailey 2009

- Shana Lutker and Steve Berrens 2009

- Tilman Hoepfl and Carl Suddath and here and here 2009

- Kay Rosen 2004

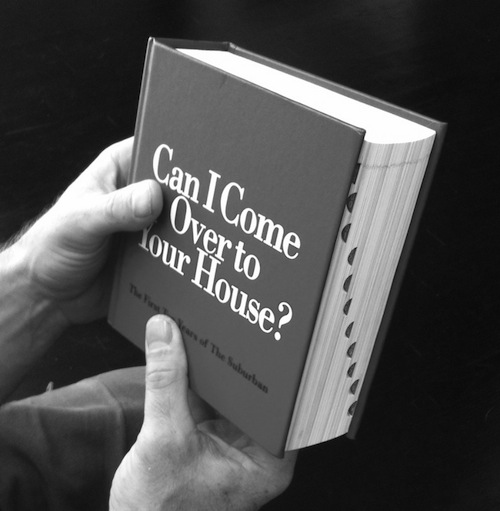

CAN I COME OVER TO YOUR HOUSE:

with essays by Forrest Nash and Michael Newman. Design by Jason Pickleman. |

THE SUBURBAN, THE EARLY YEARS 1999-2003available atWoodland Pattern Book Center |